Bradley Cooper’s elegant, ambitious biopic is a symphonic love story with sparkling, awards-worthy performances

Composer, conductor, musician, cultural titan, and at least in a parallel cinematic universe, mentor to Lydia Tár, Leonard Bernstein’s baton is a weighty one for any filmmaker to pick up. Big names have had a crack at it, with Scorsese and Spielberg each once attached to this long-gestating biopic, but it’s finally found the perfect foil in Bradley Cooper. He throws himself into the twin duties of directing and playing the man himself on-screen with the kind of no-stone-unturned dedication that would leave you unsurprised to discover that he’s bashed out a couple of symphonies himself as prep.

Wisely, Cooper’s screenplay (co-written with Spotlight’s Josh Singer) eschews the conventional biopic logic of plodding along as Bernstein’s career takes shape on the stages of New York, and fame, fortune and Hollywood commissions follow.

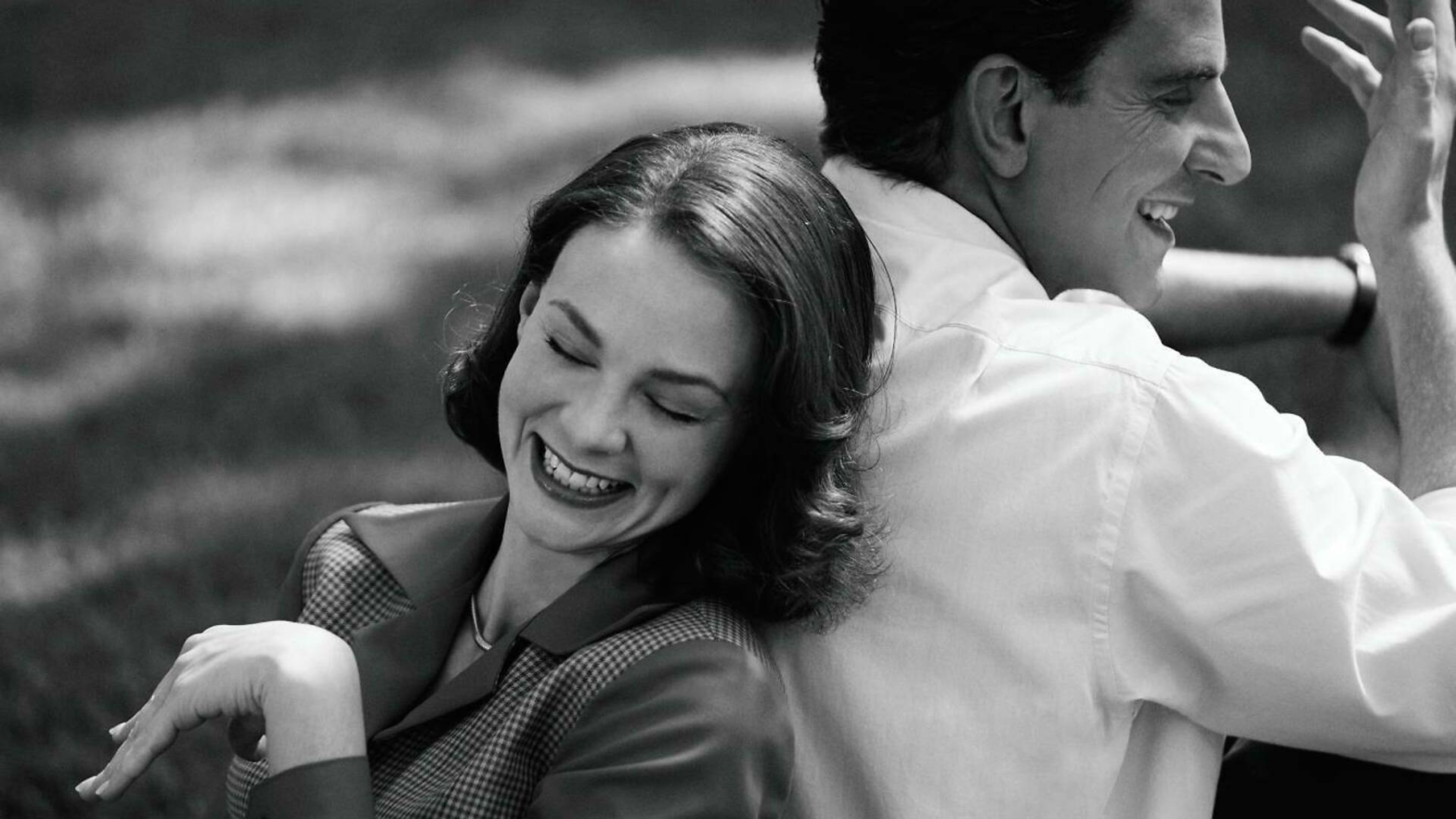

Instead, Maestro zeroes in his vivid, knotty life-long love affair with Chilean émigrée Felicia Montealegre, played with a rare mix of porcelain poise and nuggety resilience by Carey Mulligan. It’s a strange thing to say about an actress with umpteen film credits behind her, but the Shame star is a genuine revelation here: from wannabe stage starlet with the crisp elegance of a European princess, to an emotionally careworn, half-abandoned wife and mum rattling around in a Connecticut mansion, she’s the beating heart of the film and consistently defies its irksome habit of relegating her to second fiddle.

Cooper, too, is mesmerising. Forget the confected outrage about his supposedly antisemitic prosthetic nose (and you will, in ten seconds flat), because there’s nothing plastic in his embodiment of ‘Lenny’ Bernstein. Most of us probably couldn’t vouch for the resemblance without referring to Google images, but the voice – a nasal burr muffled further by an ever-present ciggie – and mannerisms – Cooper’s Bernstein throws himself into his music like a man caught in a whirlwind – only enrich the portrayal.

Thankfully, the actor-filmmaker’s regard for his subject never comes across as fawning on-screen. From his energised early years to a washed-out, coke-sniffing ’70s phase, the charismatic Bernstein is a man who sets the tempo from the podium but is often a beat behind in his personal life, navigating his bisexuality like a bull navigating a china shop. A look on the face of a discarded lover, David (Matt Bomer, terrific), offers eloquent tribute to his capacity for cruelty.

It’s a strange thing to say about an actress with umpteen film credits behind her, but Carey Mulligan is a genuine revelation here

There is, of course, music too – great, stirring, spirit-soaring slabs of the stuff. Maestro digs deep into the Bernstein crates to unleash some of the greatest hits (cues from West Side Story, On the Waterfront and his 1971 choral work ‘Mass’) and a few deeper cuts. A recreation of his legendary performance of Mahler in 1968 just about blows the roof off New York’s St Patrick’s Cathedral.

It’s a film for cinephiles as well as musos and romantics, with its discrete ‘movements’ mirroring the movie making style of its time frame. Early scenes are filmed in 35mm black-and-white and swirl lushly like an Ernst Lubitsch romance, while Lenny and Felicia’s stormy late ’60s patch is captured in Technicolor with longer shots that distance us from them, and them from each other. Like the man whose life it celebrates, Maestro deserves to pack the stalls.

Maestro premiered at the Venice Film Festival. It’s in US theaters Nov 22 and streams on Netflix worldwide from Dec 20.

Written by Phil de Semlyen