No, not the Billy Bob Thornton Amazon show, this is a new three-part series from directors Rob Ford and Christopher Dillon about the NBA legend known as “The Dipper.”

If the television universe had a better sense of poetry, Netflix’s three-part Bill Russell documentary and Showtime’s three-part Wilt Chamberlain documentary would have come out the same day. The Chamberlain doc would have gotten better ratings, but the Russell doc would have received better reviews, and then we would have discussed the relative merits of each type of success and come to the conclusion that judging either of them exclusively on that one measurement was reductive.

Instead, Sam Pollard’s Bill Russell: Legend premiered back in February, while Rob Ford and Christopher Dillon’s Goliath, about Chamberlain, will air through the rest of July on Showtime and associated platforms.

While the two documentaries about contenders for basketball greatest-of-all-time status are both solidly made examinations of their complicated subjects, neither is even the recent GOAT when it comes to multi-parters about outspoken NBA centers. Steve James’ Bill Walton series for ESPN holds that crown. But that doesn’t mean Goliath isn’t an entertaining if formally inconsistent attempt to give grounded human treatment to a man who is, more often than not, treated in unapproachably epic terms.

Wilt Chamberlain, as any casual hoops fan knows, is a legendary figure defined by numbers, fitting given how often he was accused during his career of being all about, well, numbers. The 100-point game. The season he averaged 50 points per game. And, yes, the 20,000 women he claimed to have bedded. Numbers are so crucial to “The Dipper” — the nickname he preferred to the facile rhyme of “The Stilt” — that he’s even defined by other people’s numbers, especially 11, the number of championships that Bill Russell’s Celtics team won, several at the expense of squads fronted by Chamberlain.

From the outside, Chamberlain was judged as selfish — even in the one year he announced he was going to lead the league in assists and he did just that — and branded as a loser, though those criticisms were mostly leveled against him when it came time to make comparisons. Like, “Here’s why Wilt Chamberlain was actually only the second-best player of all-time” or the fifth-best or the 10th-best.

So was Wilt Chamberlain actually Goliath? And if so, does that make Russell, who anchored teams that sometimes included as many as eight Hall-of-Famers, somehow David? What sense does that make? When we try looking at the entirety of Chamberlain’s life, rather than gawking at him as larger than life, does that make him better? Worse? Or just complicated?

The answer, of course, is an all-inclusive, “Yes.”

Ford and Dillon’s film tracks Chamberlain’s life from his time as one of 11 children growing up financially strained in Philadelphia, focusing on his youthful stutter and extravagant height. It traces his journey through a college career that ended in disappointment and a professional career in which he was part of a vanguard breaking down racial barriers and pushing for the kind of player autonomy that dominates today’s game. At the same time, we learn about Wilt the brother, Wilt the teammate, Wilt the lover, Wilt the Nixon Republican, Wilt the female empowerment activist and more.

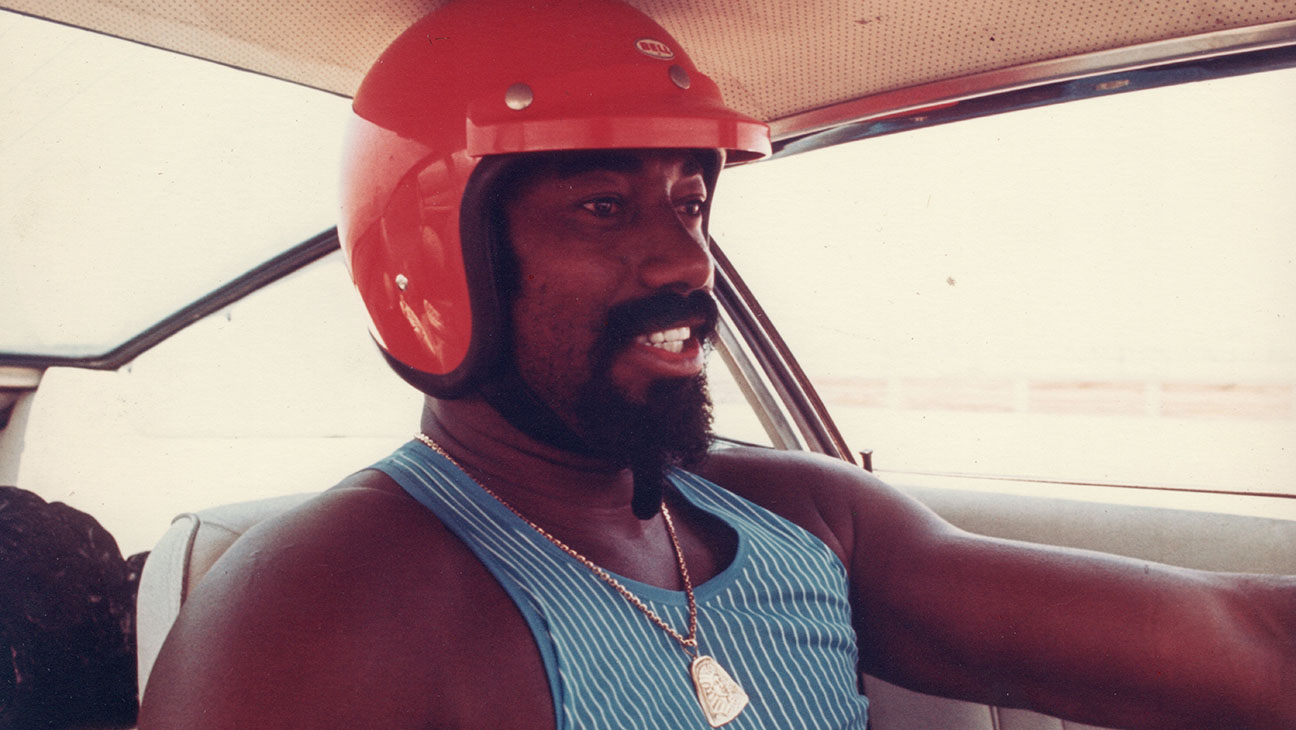

There’s a lot of Wilt and, over three hours, the directors lean heavily into available footage of Chamberlain, going back to his college days. Goliath is worth checking out for that alone, the opportunity to be reminded that Chamberlain and his jump-off-the-screen athleticism would have been unique in any generation of the sport. This isn’t one of those, “Well, it was a different era and maybe today Wilt would be a role-player and nothing more” situation. The guy jumped out of gyms in 1957 and he’d jump out of gyms today.

When it comes to talking heads, Goliath suffers a tiny bit from the recent proliferation of multi-part sports docs. At this point, I’ve now watched Jerry West tell basically the same stories in a half-dozen films since last year. Ditto Pat Riley. Ditto sportswriter Bob Ryan. Ditto USC academic — and my former grad school professor — Todd Boyd. It isn’t surprising how many people appear in both this and the Bill Russell doc. They are inextricably linked, after all. But Chamberlain retired before Bill Walton’s NBA career, and Goliath has an unexpected number of duplicate talking heads with ESPN’s The Luckiest Guy in the World.

On the basketball side though, there still are some unique and distinctive interviewees, whether it’s Tommy Kearns, who played for the North Carolina team that upset Wilt’s Kansas Jayhawks in a legendary NCAA final, or teammates or rivals like Billy Cunningham or Rick Barry. Kevin Garnett, whose Content Cartel shingle produced the series, is also an excitable onscreen presence speaking about Chamberlain’s long-term impact on the game.

Still, Goliath is at its best when it focuses on people who couldn’t appear in any other basketball documentary, whether it’s several of Chamberlain’s still-fiery sisters or a number of women who either had dalliances with him or didn’t have dalliances but want to make it clear how he treated women beyond his notorious reputation.

It’s very clear throughout that Chamberlain as a basketball star hasn’t lacked for documentation. But when chronicling him as a person, there are still potent and untold stories, like an emotional memory from the son of a former teammate that leveled me toward the end of the third hour.

The documentary naturally suffers from the absence of Chamberlain’s own voice, since he died back in 1999. The decision to have an AI program augment voice actor Michael Kunda reading Wilt’s own words in “his” voice is misjudged. This isn’t like Netflix’s recent Andy Warhol documentary, where you could imagine the recreation-obsessed artist being truly amused at being recreated himself. No, this is an affectless hollow shell of Chamberlain’s voice, not exactly robotic, but definitely stuck in a single affectless cadence, exactly the opposite of what you’d want from an effort at humanization. Maybe Garnett should have narrated? I don’t know. But this was a bad solution.

The directors had a much better solution for how to handle sections of Chamberlain’s life without available archival footage. Shadow puppetry by Manual Cinema Studios provides flavor far better than more conventional reenactments or animated sequences. I can’t say I necessarily understand why shadow puppetry was the choice, but the whimsical silhouettes are funny and evocative enough that I wish they’d been more thoroughly integrated into the documentary.

And, finally, I wish Ford and Dillon had been more committed to the intellectual approach provided by cognitive scientist Ben Taylor, who gets to do very superficial breakdowns of things like pace of play in order to put Chamberlain’s statistics into context. Anybody who knows Taylor’s work at all knows that he happily could have given detailed, nerdy breakdowns on some information that Goliath can only flit around.

Then again, I’m sure I’m in a very small minority of viewers who will get very briefly excited when the documentary begins discussing “heuristics” and then disappointed when, after defining the terminology, the concept is never mentioned again.

As I always say, a three-hour documentary series is either a feature that should have been further edited or a four-to-six hour documentary that should have offered greater depth. Goliath is satisfying enough as it goes, but maybe the legend of Wilt Chamberlain demanded that extra depth.

BY DANIEL FIENBERG